Chris Heap’s (Ottawa Club) story of over-hydration was shortened for the Summer 2016 Newsletter. His “Cautionary Tale” is reproduced here, in full. See Chris’ hiking blog at chrishe.net.

A Cautionary Tale

In 1999, immediately after I retired, I spent six months hiking the Appalachian Trail. This was the year the press were calling the “drought of the century”. Finding sufficient water along the trail was a constant worry. And I can tell you that months of uncertainty about one of life’s most basic necessities is an enduring lesson in what is important and what is not.

In spite of this, I persisted. At the end, one must summit Katahdin before October 15th – I was running out of time. After a solitary evening of serious reflection at the Carl Newhall Lean-to, with only 78 miles to go, I finally decided to call it quits for this year. I was disappointed, but not excessively so. I knew I’d done the intelligent thing. Having walked 2082 miles, I knew I could easily and more enjoyably walk the remaining 78 next summer when I wouldn’t have to face a deadline and the weather would be better.

I returned in July 2000 to finish my hike. After a gentle climb up the approach to Gulf Hagas Mountain, I spent another night at the Carl Newhall Lean-to. It was very different now. It was hot. I was up bright and early next morning for what was to be a busy day crossing the Whitecap range. I was not long into the climb before I realized things were very different. At this point last year I was trail hardened and tough. Now, nearly a year of lazy city living had softened me. I hadn’t trained enough and I was finding it hard going. My pack, which I knew for a fact was lighter than last year, felt a great deal heavier. It was a hot, hot day, just like those parched ones I remembered so well from last summer. But here was another huge difference. Here were plentiful springs of pure, cool, mountain-fresh water! The water was gushing right out of the rock so it could be guzzled down as fast as you could drink. I suppose I knew I didn’t need it, but it was so refreshing! I stopped at three or four of these springs and not only guzzled my fill but also replenished my two-litre Platypus so I could drink more as I was walking.

After Whitecap Mountain itself, I set off down the steep descent to Logan Brook Lean-to, my destination for the night. I was tired when I arrived, but I had no idea that anything was amiss. Not long after I stopped walking I suddenly felt dizzy, faint, and nauseous. I wobbled around for a while and tried to retch but nothing came up. I then staggered back to the shelter where a kind young couple gave me some hot chicken soup, and I felt marginally better for a while. The last thing I remember was deciding to lie down, but not even having enough energy to blow up my Thermarest.

When I woke up I was in very unfamiliar surroundings, and I knew with a serious shock that this was bad, very bad. It quickly came to light that I was in the ICU at Bangor Hospital. Gradually the whole frightening story emerged. Apparently I’d had a seizure around 8:00 pm and passed out. I’d spent the night being nursed by Mark and Kathy, the same generous young couple who offered me the chicken soup, while two hikers, Greg and Cullen set off in the dark, hiked back over the whole Whitecap Range (which they’d already crossed once that day), then walked out another six miles along a logging road to Katahdin Iron Works, where they phoned for help. By about 6:00 am, a team of paramedics arrived and, blissfully unaware, I was hoisted up into a hovering helicopter and flown off the Bangor Hospital. I was in a coma all that day and night and it was sometime the next morning when I finally woke up – I’d been out cold for a full day and a half!

The doctors were genuinely puzzled for a while by my condition. When I’d arrived my blood sodium level had been so low they could hardly measure it on their normal instruments. So they’d quickly diagnosed hyponatremia, which is the merely the medical word for low blood sodium. So with prompting from the doctors, I gradually recalled my ludicrous behaviour at those mountain springs two days before and the mystery was solved. The diagnosis was now simple – dilutional hyponatremia: water poisoning. Who ever knew that water could be deadly poison if taken in excess? I certainly didn’t. I knew from personal experience all about dehydration and the great importance of drinking enough, especially on hot days. I also knew about electrolyte replacement, which was why I was carrying Gatorade powder. But I’d never recognized its vital importance, which is why I hadn’t wanted to spoil the taste of that pristine water by using it.

So I nearly killed myself by over-hydration and on a previous occasion, I’d suffered serious heat exhaustion from dehydration. In very hot weather, how could one stay in the safe zone? Of course you can stay indoors (or maybe go biking) on very hot days, but for very keen hikers like me this isn’t an option. The answer is deceptively simple – just listen to your body! I believe the body has a kind of wisdom all of its own which, if you will trust it and take it into account, will not often mislead you.

So how does my method work in practice? On very hot days, in addition to a plentiful supplementary supply in my pack, I carry two half-litre bottles – both of which are equally easily accessible without stopping. One contains pure water and into the other one I drop a Nuun electrolyte replacement tablet (no added sugar). Then as I’m hiking I simply drink from whichever container my body tells me it needs. I think it’s important that both bottles are equally accessible and taste equally good, so your mind has no reason to interfere.

Heroes of this tale: first and foremost those intrepid young men who hiked all through the night to get help; the generous young couple who nursed me through the night; the brave paramedics and helicopter crew who risked their lives hovering their craft in that dangerous canyon over Logan Brook Lean-to; the attentive and competent staff of the Bangor Hospital, and my son who interrupted his studies at MIT to be by my side.

Two morals. First, is “listen to your body”. When your body is trying to tell you something, take heed. Never ignore it or capriciously overrule it. The second moral is “moderation in all things”. By nearly killing myself I’ve demonstrated it does literally mean “all things” – even something as salubrious as pure mountain water.

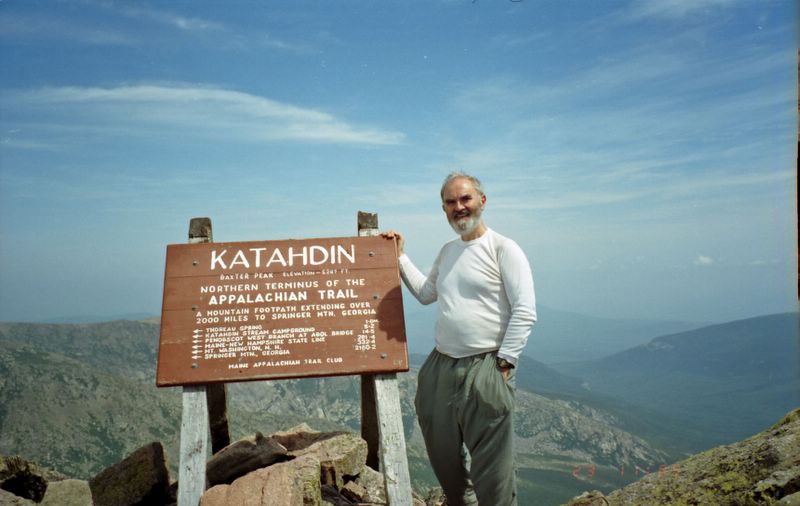

The happy ending: By the next year (2001) I’d moved to Ottawa from the dreary plains of Indiana. I now had the Gatineau Park on my doorstep to encourage me to prepare. So in July 2001, with the companionship and support of my new friend Alex Macdonald, I easily accomplished that last 78 miles and crowned it with a memorable ascent of Katahdin on a gloriously beautiful day. I was on top of the world and I counted myself very lucky to be alive.

Want to learn more about overhydration? Be sure to read the article, “Too Much of a Good Thing” by Dr. Tom Welch, in the January-February 2016 edition of “Adirondac,” the Adirondack Mountain Club’s magazine. There are other items from Dr. Welch on his website and his blog adirondoc.com.